LIFE IN A “CAGE”: MEMORIES OF A GIRL FROM KARABAKH

Thoughts on the margins of Gunel Movlud’s autobiographical novel “The little girl from Karabakh“

Sevil Huseynova

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, societies of the South Caucasus faced the phenomenon and repercussions of mass forced displacement. The new word “qaçqın” (refugee) entered the everyday lexicon– for too many people, it became synonymous with unwanted guests. The public’s attitude towards refugees varied widely, ranging from expressions of sympathy to loathing; from willing support to reluctance to engage whatsoever.

Unlike many Bakuvians, I have had personal, first-hand experience with refugees. My parents accommodated a young family from Jabrayil at our dacha: a father, mother and their three children. They were from the very district where the author of the novel, Gunel Movlud, lived before the conflict. I spent time with them every weekend at the dacha. Often, these meetings were accompanied by nostalgic stories of the old, peaceful life. The family from Jabrayil believed that sooner or later they would return to their home. They lived at our dacha for about ten years, until they built a small house of their own nearby. Their dream of return was put on hold for decades.

The subject of refugees from Armenia and Azerbaijan came back into my life much later, during a study that my colleagues and I conducted in the countryside. As with many countryfolk, the refugees I interviewed were often stingy with words; but, they compensated for terseness with colorful and emotional memories of life in their native villages. In each anecdote, long or short, a never-ending sense of dislocation was conveyed. These were the stories of people who lost their homes and were forced to abandon their usual way of life. There were hundreds of thousands of such people in a small country — a situation that can be measured only with the phrase “social catastrophe”. So far, this tragedy has not given birth to a text worthy of its scale.

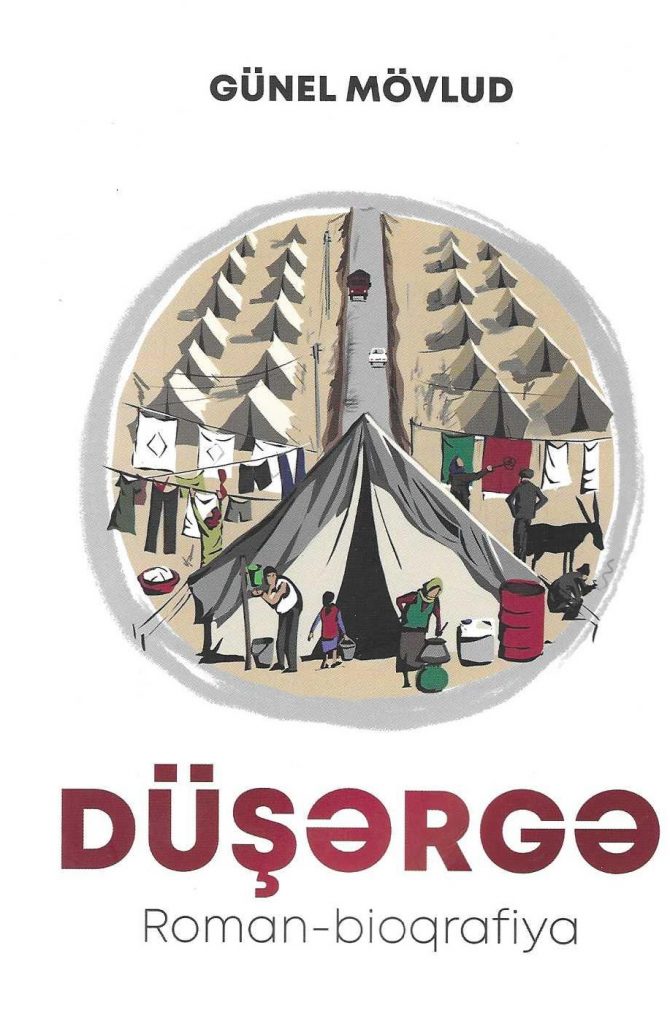

In her book The little girl from Karabakh (Девочка из Карабаха in Russian, Düşərgə (the Camp) in Azerbaijani), journalist, poet, and translator Gunel Movlud tells us with utmost frankness how her family and their fellow villagers lived in a tent city in the bleak desert of Sabirabad District, directly bordering Iran. This autobiographical novel is written in the form of diary entries, through which the author seeks to reconstruct events that happened to her and her loved ones more than twenty years ago.

Gunel was a child when her family, relatives and neighbors were forced to flee their native village in Jabrayil District of Azerbaijan. The memories of an eleven-year-old girl are interwoven with narration of her difficult relationship with a cruel and indifferent father, and the strict rules of everyday life in an atmosphere of obtrusive and very tight social control exercised by family and neighbors. Life in her village was far from idyllic, but there was a roof over her head in that past life before the war and ensuing hunger.

The refugee camp was a space divided into “cages”: cramped canvas tents for houses, and a well with brackish water at the bottom for the fridge. There was one restroom for dozens of families and no chance of privacy, as the tents were separated only by two meters. Your life, just like those of your neighbors, was out in the open for everyone to see and hear from dusk to dawn. Hopes for a return, very strong at first, faded with each new year spent in the desert wasteland, as the tents began to feel like home. Families were started, children were born, and a new cemetery grew. Among these explicit memories are many pages about the violence and cruelty of men towards women and children, and towards each other. There are also many examples of self-sacrifice and mutual aid. These are stories of ordinary people trying to reconcile their old communal customs with their new “qaçqın” status, which bore little resemblance to their pre-war lives. Reading Movlud’s novel is like touching a still-open wound that will never be fully healed.

This is a novel about hardships and labors of the camp: an old tent with holes donated by the Iranians, a hut made of reeds assembled by hand, a single tree grown in the desert, a single toilet shared by dozens of people—if you were lucky enough to get in. Men gave women little peace and even fewer freedoms. Meanwhile, a larger tent served as the school, where you were taught that reading is a waste of effort, and time would be better spent fighting for water that could only be drawn from a common tap for a few hours a day. This strange life filled with horror and resilience transpired—all of it remembered as home, as a place that is missed when you finally leave. Ultimately, this novel explores how you can get used to the camp, or the “cage”.

Movlud’s poignant refugee text is often criticized for its lack of commentary on the “enemies” and the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. It is criticized by professional patriots or even supportive readers. In any case, the novel is criticized for its strongest point, from my view. The story of a little girl from Jabrayil District living in a refugee tent city could just as well be told by a little girl from a different country, from a different conflict and, probably, from a different time. This novel’s universality speaks to all who have lost their homes and are painfully trying to preserve remnants of their dignity and hope for a better life.

If Gunel Movlud managed to escape the confines of the “cage”, then many others like her have a chance, and the hopes expressed by this novel cannot be in vain.

The book The little girl from Karabakh was published in Azerbaijani and Russian in 2020 and 2021 respectively, and it has aroused interest among a wide range of readers in Azerbaijan and other post-Soviet countries. Translating Gunel Movlud’s novel into English will enable an even wider range of readers to learn about the struggles of refugees, through the eyes and voice of a girl who lived in a tent city for five long years.