Journalists, civic activists and social researchers from post-Soviet countries wishing to contribute to the peaceful conflict transformation often lack the necessary skills. Most fail to get rid of propaganda clichés, hate speech and enemy images.

Kharkiv, 2019. Photo by Sergey Rumyanstsev

Each post-Soviet conflict has its own specifics, but they also have many similarities and similar consequences. For example, popular conflict discourses allow one to see only 'one's own' losses and refuse to recognize the losses of the 'other' side. The traditions of mutual support and the memory of peaceful coexistence have been totally ignored and repressed by that approach.

Severodonetsk, Luhansk oblast, Photo by Vadim Lure

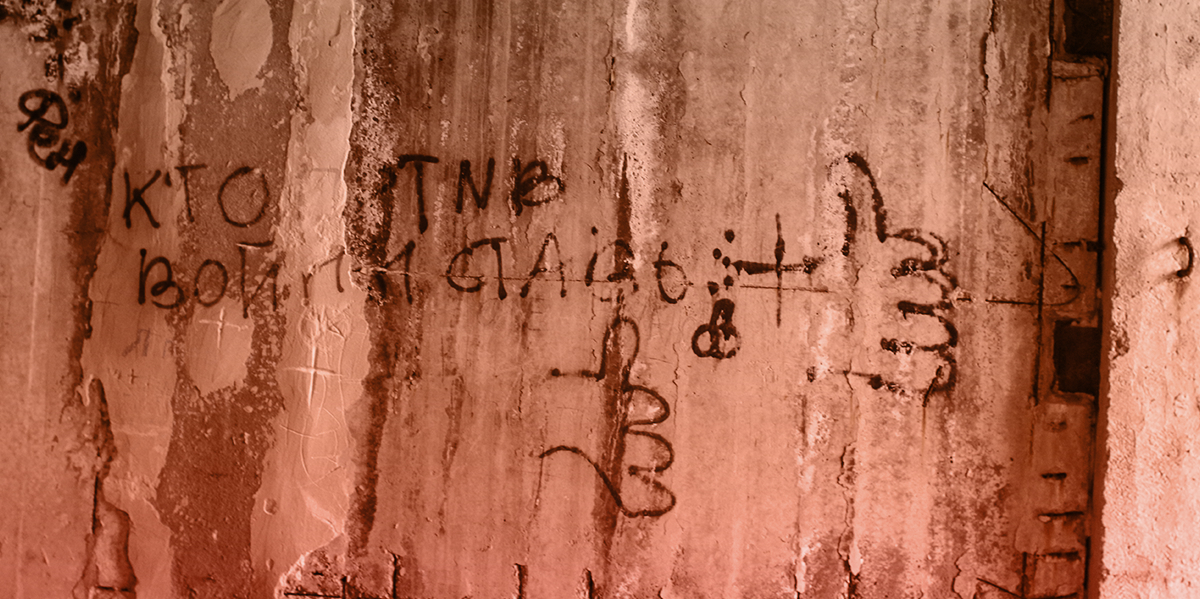

Memories of peaceful daily life, conflicts resolution at the level of civil society are often excluded from public space.

Severodonetsk, Luhansk oblast, 2019. Graffiti in an abandoned unfinished building. Photo by Vadim Lure

A retrospective rethinking of the past enables to represent conflicts as "historical". Increasingly popular nationalist retrospective discourses and practices are aimed at deepening confrontation. Such trends can be observed in the case of very different and, at the same time, very similar conflicts in the East of Ukraine, Nagorno-Karabakh, Abkhazia or Yugoslavia.

Severodonetsk, Luhansk oblast, 2018. Photo by Vadim Lure

Conflicts are accompanied by the large-scale destruction of various sites of memory (national theatres, schools, monuments, different architectural structures), mass renaming of streets and squares. For example, in modern Baku and Yerevan there is almost no evidence of long cohabitation of Azerbaijanis and Armenians. In the context of the conflict in eastern Ukraine, there is a massive change in toponymy and many monuments are being destroyed.

Former Armenian Apostolic church, Baku, 2019. Photo by Natalia Yosef

Reconstructions of socio-cultural landscapes often become an integral part of the policies of constructing enemy images and contribute to the permanent deepening of conflicts ("war of memory", "war of toponyms"). Such practices rapidly turn into instruments of control over public spaces and populations and become a powerful obstacle to democratization necessary for peaceful conflict transformation.

Courtyard in former "Armenikend", Baku, 2019. Photo by Natalia Yosef

This policy has its downside. It creates new sites of memory, new heroes, constructs new discourses and rituals designed to commemorate modern conflicts. In a situation of growing militaristic sentiments, all these new sites of memory and discourses also tend to displace the memory of peaceful coexistence, ignoring the rich experience of problem-solving at the micro level.

Celebration of May 9, Luhansk oblast, 2019. Photo by Sergey Rumyanstsev

The one way to counter these trends is to participate in international networks aimed at creating an alternative to the conflict discourses which dominate the public space. These are strategies for the public presentation of the results of joint work in international groups, whose participants are citizens of conflicting countries.

Moscow, 2019. Photo by Sergey Rumyanstsev

Local administrations, various public institutions and most NGOs are reluctant to contribute to the integration processes of migrants and refugees. There are many reasons for such passive attitude and one of the most important is the lack of requisite experience. Often local authorities and civil society representatives are not able to properly manage their own resources, establish effective communication and mutually beneficial cooperation.

Temporary housing for internally displaced persons. Kharkiv, 2019. Photo by Sergey Rumyanstsev

Many institutions seemingly far from the migrant and refugee agenda (e.g. museums or libraries), on the contrary, have proven to be very effective agents of integration. No less effective can be different art initiatives at the civil society level and with the support of local administrations.

Rostov-on-Don, 2019. Photo by Sergey Rumyanstsev